“When I saw that, I thought it was such a great pairing between revolution and nirvana,” said the photographer Jordan Doner, whose new show “A Revolution in Luxury” opened on Thursday at San Francisco’s Serge Sorokko Gallery. “It wasn’t necessarily a dig at middle American consumerism, but actually the refined person who apparently had some design sense and intellect.”

The idea stuck with Doner, so much so that he ended up calling an Italian countess friend and soliciting the help of her groundskeeper to conduct controlled explosions. Then he retreated into the desert with several more friends, a camera, and a collection of the limited edition Louis Vuitton purses designed by Takashi Murakami and Richard Prince — and began blowing them up.

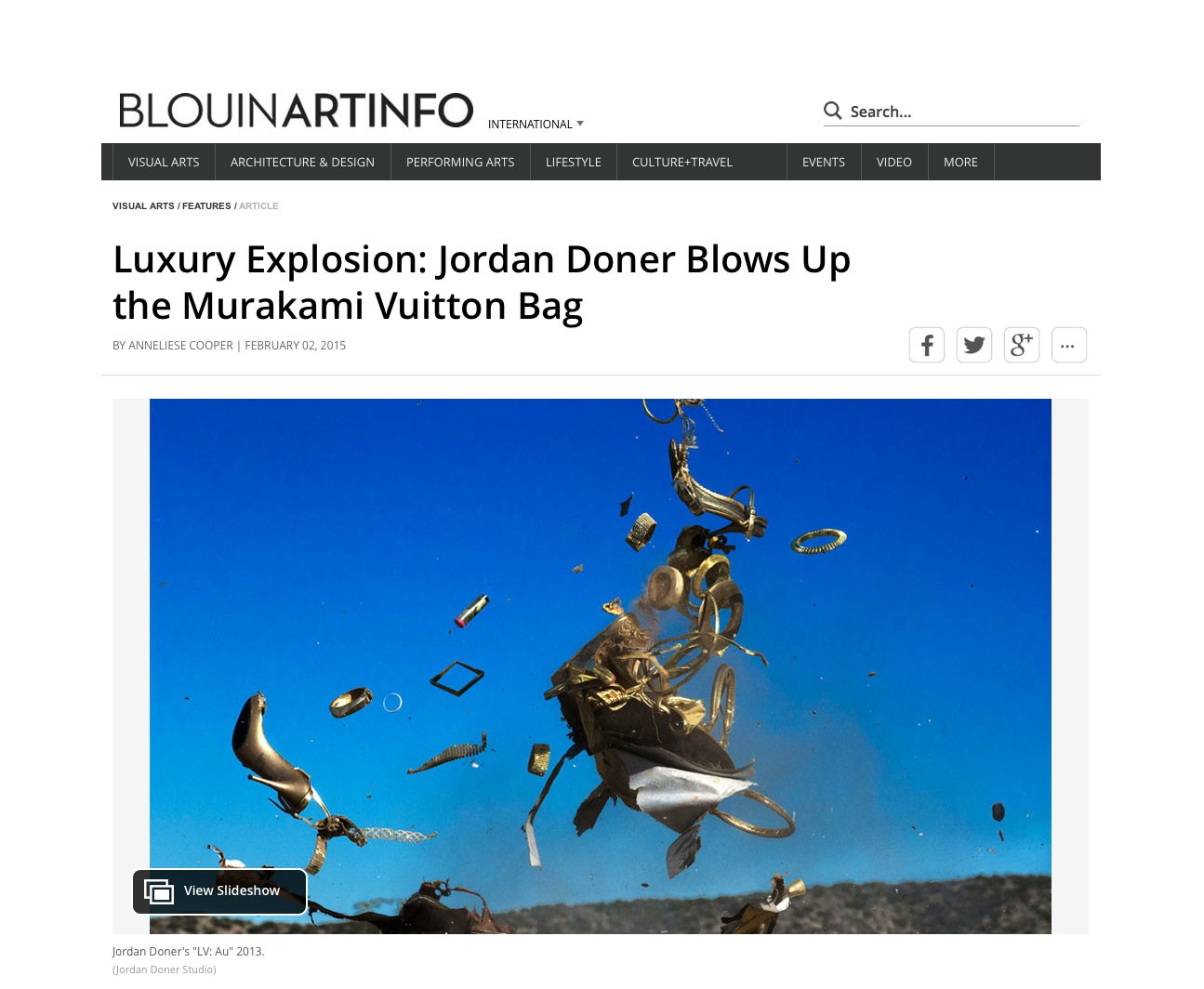

“When I first did it, I missed a lot, because we were doing it Wylie Coyote style — literally lighting a fuse and running,” he said. “But then I would just stuff all of the mistakes back into another bag, so when finally I caught something there was a lot of debris.” Bag bits joined high heels and other forms of “luxury shrapnel” in adding heft to the detonated purses; by his second explosion excursion last year, Doner was testing the melting point of silicone breast implants that an avid collector of his — a plastic surgeon — had donated.

So why the Vuitton bags? Partly, he says, they’re a result of trial and error. Doner initially tried blowing up fashion magazines, which fizzled, and caviar, which reportedly did better, but not nearly as well as the purses. “If you’re looking at it from a humanistic point of view, [the bags are] very crass and very commercial, but they’re also quite beautiful,” he said. “When you blow them up, what’s interesting is they just become these incredible formal studies. And an accident that happened is, the guy who did the detonations was able to do it without smoke, so they just hang in the air, and they almost look like collage.” Indeed, one photo taken against a cloudy white backdrop appears at first glance to be a pixelated post-Internet image, its jagged shapes seemingly born of Photoshop selection tools instead of thousand-dollar leather scraps.

But of course there’s also an idea behind the destruction of all that crass commerciality — one he seems to have doubled down on with his second series, which also includes exploded replicas of a Donald Judd box and of Jeff Koons’s “Equilibrium Tank” (in which the two familiar basketballs surge up against a rush of displaced water, pieces of glass aquarium splitting off at the sides).

It’s not that Doner means to condemn the commercial art market full stop: “Art has always been sold as something for humanity, but it’s actually a vessel of wealth and prestige, commerce between a very tiny band of the elite — so it’s ripe for a staged revolution,” he said. “But, you know, I wouldn’t endorse an actual revolution.”

“I think the self-righteousness of the creative community is just as debilitating as in other communities,” he added. “So this is a look at how awesome it feels to be self-righteous, and how awesome revolution looks and feels, but it’s also an acknowledgment that we all want that abundance. It’s such a caricature of desire, but nonetheless, I have it.”

He acknowledges that his background in commercial fashion photography lends a sense of “luxury campaign style” to these objectively violent images. “So, the interesting issue is, if there’s revolution and then there’s utopia, is the utopia that I’m staging utopia after the revolution, or is it sort of the reason to have a revolution?”

This idea of utopia is an overriding theme of the show at Sorokko, which Doner has planned as a sort of “Hieronymous Bosch ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ with Puckish creatures” infused with “a ’60s B-movie-poster idea of sexual abundance and utopianism.” In addition to photos and videos of the explosions, as well as some of the actual debris, he’s displaying his series “Staged Utopias: Landscapes, Lifestyle, and Artifacts,” which includes models wearing nylon bodysuits printed with vintage newsprint-like images of naked bodies, the naked-but-not-naked aesthethic hammering home “the idea that utopia’s just always slightly out of reach.”

Doner cops to his retro inspiration: “I think the last big push in our culture where people believed without irony that we could attain something was the counterculture that grew out of the ’50s and really blossomed in the ’60s — and I feel like we definitely got tangible results from that, major tangible results. Now, things are more measured and ambivalent.”

While it may be tempting to read that same ambivalence into his photos — a still, formal tranquility imposed upon the satisfying bang of destruction — they are ultimately, to borrow his term, “seductive,” a fantasy dismantling of fantastical consumerism, as much a tease as the fake-nude suits. But it’s still satisfying, on some level, to know that real luxury was harmed in the making of these images — like Antonioni’s explosions, couched in the safety of a dream sequence, playing on some latent desire to watch beautiful things burn.